Frederick Hockley

The First Missing Chapter

To

introduce Frederick Hockley, it is enough to say that we do not have a

baptism certificate for him, only this natal chart. After thoroughly

searching through all the parish registers of English dioceses available

online, I could simply conclude that the record of his baptism has been

lost.

Alternatively, following a vague reference in a letter he wrote to his friend Francis George Irwin on May 18, 1875:

When I first began keeping a diary, my visions were Unitarian, with Jesus as an inspired man — but after reading C.A.’s teachings, they suddenly shifted to a ∴ [Trinitarian] God — the divine birth of Jesus and their Holy Spirit.

I could also hypothesize that his family followed Unitarian beliefs. This is more wishful thinking than anything else, since Hockley was likely referring to the content of his visions in the crystal, rather than his personal religious convictions.

After

the Hardwicke’s Act of 1753, which aimed to prevent clandestine

marriages, all unions between a man and a woman in England had to be

solemnized exclusively in the churches and chapels of the Church of

England, after obtaining a license from an Anglican priest. This

effectively outlawed the rites of nonconformist denominations, whose

registers, already rare before 1753, almost entirely disappeared

afterward.

Many Unitarians complied with the law by marrying formally

in the Church of England and then privately holding the ceremony within

their own congregation. However, not everyone accepted this compromise

for the sake of peaceful coexistence. A minority continued to marry

according to their own traditions, asking at most that the union be

recorded in registers kept by a dissenting minister. Nevertheless, this

did not prevent issues regarding inheritance and the legitimacy of their

children.

As for baptism, Unitarians continued to administer the

sacrament to children in private, within a meetinghouse or the

minister’s private residence, although the ceremony often resembled more

of a blessing than a full religious rite. Other groups abandoned infant

baptism altogether, opting instead for dedication or acceptance into

the community.

If Frederick’s family were indeed part of this

context, it is not surprising that no written record of his birth

exists. It seems even more likely when considering that, when it came

time for marriage, Frederick chose a civil ceremony, avoiding Anglican

churches altogether.

Fortunately, to compensate for the lack of official documents, Hockley himself provides some assistance. Frederick left behind a considerable amount of handwritten material that contains valuable autobiographical hints. Scattered throughout the marginal notes of books he read, the transcripts of his spiritual diaries, and his correspondence, are pieces of information that are useful for reconstructing his life.

Uranoscopia, or the pure language of the stars, unfolded by the motion of the seven erratics, &c. is a work by Ebenezer Sibly, which may not have been published. There is only one known copy in the Wellcome Collection.

It is a compilation of tables and blank forms for the reader to

complete, guiding them in the creation of horoscopes, all adorned with

elaborate engravings.

The copy held at the British Library, possibly a

prototype left in draft form, was given to Hockley by Denley in 1833.

The pencil-written data filling the forms are likely in the handwriting

of the recipient. The natal chart mentioned earlier can be found at the

beginning, and towards the end, after about a hundred blank pages, there

are other intriguing birth charts. That of his mother:

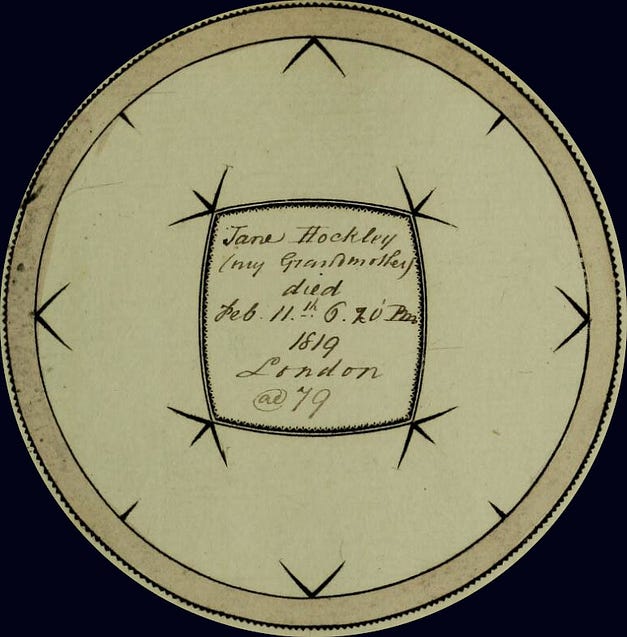

And that of his paternal grandmother:

Here, we have precise and detailed information:

Ann, his mother, died on September 22, 1822, in London.

Jane, his grandmother, died on February 11, 1819, in London at the age of 79.

In the burial registers of St. Leonard Shoreditch, with nearly identical data, the following burials are recorded:

Anne Hockley of Luke Street, 44 years old, buried on September 22, 1822

Jenny Hockley of Luke Street, 82 years old, buried on February 21, 1819

There is a discrepancy in the birth year of Jane (Jenny): 1837, declared at her funeral, or 1840, as remembered by her grandson Frederick.

Now seems like a good moment to point out that the coordinates of Luke Street are 51° 31' 26.8" N, 0° 04' 57.8" W.

A search through electoral registers, property documents, and tax lists does not cross-reference any Hockley families on Luke Street during those years, but reveals that the area was full of Hockleys. For example, there was a William Hockley on Old Street Road between 1821 and 1825. At the same time, another William Hockley lived on Leonard Street, a surgeon, son of William and brother of Samuel Hockley, a tea dealer from Bishopsgate.

In another situation, I would attempt to track down Frederick’s parents’ marriage, but based on the failure of the baptism investigation, I do not expect any definitive results.

Frederick

was born in 1809, and his parents likely married a few years earlier,

presumably of age, which would make their birthdates around 1775.

Following the same reasoning, his grandparents’ marriage was likely just

before this.

Searching online marriage records, including so-called

non-parochial ones, between a Jane and a Hockley between 1765 and 1780

produces a likely incomplete list:

William

Hockley and Jane Robarts of St Leonard Shoreditch, who married on

August 31, 1766, residents of Flyinghorse Yard, had the children:

John, born on June 17, 1769, but died just over a year old, buried on October 14, 1770,

another John, born on August 19, 1771.

Robert Hockley and Jenny Nelkins married on August 13, 1769, in Newchurch, Hampshire, and conceived Robert on June 2, 1771.

John Hockley and Jane Kirby, both from St. George Hanover Square, married on November 24, 1770, children:

Jenny in 1776, baptized in Teddington, Middlesex,

Samuel in 1778, also in Teddington,

Richard in 1782, baptized at St. James, Piccadilly.

William Hockley and Jane Stapleton of St. Giles Norwich, who announced their marriage on September 22, 1776, of which no male children have been found.

Joshua Hockley and Joanna Child, both from St. George Hanover Square, married on May 15, 1777, apparently also childless.

From these results, we can derive a very incomplete list of potential fathers for Frederick:

John and Robert from 1771,

Samuel from 1778,

Richard from 1782.

Perhaps one of them married an Ann(e) in Middlesex between 1790 and 1810. Indeed, something does emerge:

Richard Hockley and Ann, 1790 — London

John Hockley and Ann Wordsworth, January 23, 1791 — St George, Hanover Square

Robert Hockley and Hannah Currey, July 30, 1797 — Saint Bride Fleet Street, London.

However, all of these cases are problematic.

If

the Richard who married in London in 1790 was the son of Jane Kirby

from Teddington, he would have been just eight years old at the time of

the marriage.

When John married Ann Wordsworth, he was just one year

shy of the legal marrying age, and perhaps he obtained parental

consent, though I doubt Ann’s parents would have allowed it, since their

daughter was only thirteen at the time.

Robert’s marriage in 1797

does not have any age discrepancies between the spouses, but there are

doubts about the locations. The possible father of Frederick was born in

Hampshire, and his marriage took place in a London parish different

from the one in the northern part of the city, between Old Street Road

and Shoreditch, where the family seems to have lived, raising doubts

about the match.

In the Beckenham church cemetery in Kent, the graves of Sarah, Frederick’s wife, John Hockley (1772–1838), and his wife Jane (1773–1802) are buried together. It would be easy to assume that this John was Frederick’s father, but it is not that simple.

Frederick

is a significant figure within a small circle. For those interested in

the history of esotericism, occultism, spiritism, or spiritualism,

Hockley is a key figure in the Victorian revival and serves as a bridge

between early nineteenth-century figures such as John Varley, the 4th

Earl of Stanhope, Robert Cross Smith, and members of the Mercury

Society, and the late-century spiritualists as the already mentioned

major Irwin, Benjamin Cox, W. R. Woodman, William Wynn Westcott and all

those who contributed to the birth of the Hermetic Order of the Golden

Dawn.

Frederick was convinced that he could communicate with the

afterlife and with pure spirits who had never incarnated. He was

initiated into the practice at the age of sixteen and continued it more

or less consistently throughout his life. At one point, he began to keep

a record in which he documented the descriptions of the spirits he

communicated with, the questions he asked, and the information he

received from them. He often told his correspondents that he had

collected thirty volumes of notes, containing over twelve thousand

responses, carefully stored under the title The Crystal: A Record of Visions and Conferences with the Inhabitants of the Spirit World.

In

these conversations with spirits, whether summoned or spontaneous,

Hockley occasionally referenced his family. Below are extracts

concerning his father, in which, through various mediums’ visions, he

received spiritual advice:

March 22, 1853

Frederick Hockley: What about my father?

Emma Louise Leigh: Don’t go to him. If you do, you will get into

serious trouble. His age makes it impossible for him to stay around much

longer, but he will remain among you for a considerable time. I cannot

tell you how long because spirits have no concept of time.

May 2, 1854

Note by FH: Some years ago, I removed two pages regarding private matters about my father.

May 30, 1854

FH: I have received this again from S. H.

ELL: I sincerely hope you don’t do it. The future seems brighter

regarding your father; a heavy calamity that was hanging over him

appears to have been lifted, and I have reason to believe that soon he

will leave this world much happier than his current state would allow.

June 20, 1854

FH: I would like to say something before I leave.

ELL: If you receive a letter from Bir.gham, be doubly careful not to

reply until you have communicated with me. If you feel it necessary, you

can call me in this mirror when you receive the letter. I’m not saying

this letter will actually arrive, but it is the intention of the parties

that it does. Your father is more at ease now than he has been in the

recent past. In fact, he is losing so much of his faculties that he is

becoming almost insensitive to both pain and joy. I’m sorry to say that

his wife’s eldest daughter is rapidly following in his footsteps.

February 20, 1855

FH: I don’t need to say how much I suffered because of my father’s

insanity — this was something I had foreseen for a long time, and since

it was out of my control, I can only say that it was fate. However,

thanks to your advice, I haven’t suffered as much as I certainly would

have, had it not been for this. I cannot…

March 20, 1855

FH: I received this letter from a friend of my father. Could you advise me?

ELL: I am still of the opinion that the greatest service you could

render him would be to remove him from his family. But you must ensure

he is completely separated, so that the comforts he receives are not

withheld by them. I would advise against increasing the money you

usually lend him, but at the same time, I hope you won’t allow his

affairs to torment you. It’s not good for him, and it’s bad for you.

Believe me that what you have done is for the best, and I will always be

ready to offer any advice when you feel the need.

After the death of his young medium, Emma, Hockley turned to Charlotte, wife of his dear friend Henry Dawson Lea.

January 24, 1860

CL: Have you heard from your father?

FH: Yes, last week, from a friend who informed me that he was 82 years old, doing well, etc.

CL: It doesn’t seem like today, but very soon, he will die.

FH: I had hoped for certain reasons that he could last a few more

years, but in case of his death, nothing on Earth will make me worry

about his wife or his family.

CL: It is my wish that you do not.

March 13, 1860

FH: What about my father?

CL: I think I’ve already informed you that he will die soon.

From early 1862, and for just a few months, Hockley relied on a professional medium, Madame Louise Besson.

April 15, 1862

FH: Any advice about my father?

LB: Not now, but I will remember to look again if you ask me later.

FH: Another Tuesday, you mean?

LB: Yes. I will examine the old man and let you know.

FH: Can I ask you next Tuesday?

LB: You can. If I’ve done the work, I’ll answer; if not, I’ll delay it and say he is a very strange man.

April 22, 1862

FH: What about my arrangements for my father?

LB: Exactly. Do your duty, and God will do His.

These

entries, in addition to offering a window into the deep and sometimes

troubled relationship Frederick had with his father, highlight how

between 1853 and 1862, Frederick’s father was still alive.

It follows that the John Hockley buried with his wife, who died in 1838, cannot be his father.

More importantly, it tells us that in January 1860, he was 82 years old, meaning he was born in 1777 or, at the latest, 1778.

Other details, though less certain at this stage, gain significance when combined with others: his initials may have been S. H.; despite suffering from poor health at the age of 75, he survived at least another seven years; he had another family with whom Frederick seems to have had poor relations; he may have lived in Birmingham.

At this point, suspicions focus on Samuel Hockley.

The

son of Jane Kirby, his birth date matches. It is true that I have no

proof of his marriage to Ann, Frederick’s mother, however…

Looking

into the life of this Samuel, it emerges that after his baptism in

Teddington on August 28, 1778, he seems to disappear from official

records — at least until 1829. This documentary gap might be explained

by his possible Unitarian faith, meaning that any marriages or children

he may have had up to that point could have left no written trace. He

reappears in connection with a marriage in Birmingham.

On July 17 of

that year, a marriage was recorded at St. Martin’s Church between Samuel

Hockley and Mary Ann Wilson, both widowed. A few years later,

apparently widowed once more and still without children, he remarried

yet again — once again at St. Martin’s — this time to Ann Whitworth. She

was twenty; he was fifty-seven.

Their union lasted nearly thirty

years, and though no longer young, Samuel proved quite prolific: he and

Ann had eight children, two of whom, however, did not survive long.

A

story passed down among their descendants suggests that Samuel and Ann

led a rather extravagant lifestyle and that a son from Samuel’s first

marriage traveled from London to strongly criticize their way of living.

Here, I cannot help but wonder whether they were referring to our Frederick.

After

their wedding, Samuel and Ann first settled in Edgbaston, an affluent

area of the city. Tracing their movements through their children’s

baptismal records and successive censuses (1841, 1851, and 1861), it

becomes evident that they moved frequently — generally to progressively

less affluent neighborhoods. Between 1835 and shortly before 1861, they

lived in at least ten different houses. Perhaps, as one descendant

speculated, they were constantly trying to stay one step ahead of debt

collectors. This precarious financial situation aligns with the

complaints of the London-based son, who lamented — through the spirits —

his father’s incessant borrowing.

I mention 1861 as a key date marking the end of Ann and Samuel’s life together because, in that year’s census, Samuel does not appear in the family home on Farm Street, in the parish of St. Matthias, where Ann and their children were recorded. Perhaps Frederick had finally succeeded in separating his father from his despised stepfamily.

The last remaining mystery is the identity of Frederick’s mother. Who might Samuel Hockley have married between 1799, the year he reached adulthood, and 1808, the year of Frederick’s birth? As has been repeatedly emphasized, parish records are of no help in this case.

One final clue, once again from Frederick’s recorded spiritual communications, reveals that he had a brother named Henry, though all we know about him is that he died around 1840.

And in fact, I have one last possible lead, drawn from a letter Frederick wrote to Herbert Irwin on June 24, 1877, the son of his friend, Major Irwin:

I must try to refresh my memory regarding the Theosophical Society to which MN alludes — not the one Captain “Webb” belonged to, but the one that met in Hoxton. Strangely, my old schoolmaster in Hoxton was a member; his name was Webb. He was very passionate about astrology and the occult sciences, as was Bishop, the schoolmaster at Sir John Cass’s school on Church Row, as I later learned from Mr. Jno. Denley, the bookseller. I was only eight years old when I left Mr. Webb’s school.

Frederick was a Habs Boy, meaning he was a student at the Haberdashers’ Aske’s Boys’ School in Hoxton.

|

|

The

Almshouses of the Venerable Company of Haberdashers in London, also

known as Aske’s Hospital, was built through a bequest from the textile

merchant Robert Aske (1619–1689) at the end of Pitfield Street, Hoxton,

designed by Robert Hooke around 1692.

Having amassed wealth through

his work for the East India Company, importing raw silk, Aske was

admitted to the Worshipful Company of Haberdashers, eventually becoming

its Master. He married twice but had no children. Upon his death, he

left a significant portion of his estate — approximately £32,000 at the

time — to the Haberdashers’ Company for charitable purposes. This led to

the establishment of a hospital, intended to house twenty impoverished

haberdashers in need, and to provide food, shelter, and education for

the sons of twenty members of the guild. The hospital opened in 1695,

and the school followed in 1697.

The Court of Assistants selected the

children to be admitted to the school, giving preference to the sons of

liverymen but always requiring them to be the sons of freemen, aged

between seven and fourteen. In the early 19th century, the school

typically had around twenty students, only a small fraction of whom

received scholarships from the Company, and the schoolmaster was

permitted to give private lessons as well.

Around 1794, the schoolmaster was William Webb,

who single-handedly taught the children to read, write, and perform

arithmetic, while also providing religious instruction. The students

were catechized quarterly in the public chapel, read both the Old and

New Testaments, learned Watt’s divine hymns, and prayed morning and

evening in the classroom. The prayers were taken from Lewis’s catechism

for schools.

In 1820, after more than twenty-five years of service at

Aske’s School, Webb was appointed headmaster of Trotman’s School in

Bunhill Row, another institution under the Company of Haberdashers.

This suggests that Frederick’s father must have been a haberdasher. Coincidentally, the Company’s admission records include a Samuel Hockley in 1817. Unfortunately, this Samuel’s father was named William, and he turns out to be the tea merchant from Bishopsgate, whom we have encountered before — and who died in 1829.

Amanda Zimmerman, The Mysterious Manuscripts of Frederick Hockley

Notes and Discussions on Samuel Hockley

Eric Robinson M.A. (1963) Benjamin Donn (1729–1798), teacher of mathematics and navigation, 19:1, 27–36, DOI: 10.1080/00033796300202843

Second Report of the Commissioner… concerning Charities in England, for the Education of the Poor, 1819

Alison Butler, Magical Beginnings: The Intellectual Origins of the Victorian Occult Revival

John Hamill, The Rosicrucian Seer: The Magical Writings of Frederick Hockley Roots of the golden dawn series

Commenti

Posta un commento